Taxi drivers in Shenzhen power up their electric vehicles at a charging station opened by China Southern Power Grid. The environmental irony? The energy for most electric cars in China is supplied largely from coal plants. (Hal Bernton / The Seattle Times)

Each car soaks up electricity from a utility aggressively moving away from coal to get just over half its power from hydro, nuclear, solar and wind energy that emit no greenhouse gases.

“It’s very ambitious — the goal is to get cleaner and cleaner,” said Liang Xiaofeng, a China Southern Power Grid official.

Shenzhen, a booming high-tech hub of futuristic skyscrapers, is on the front lines of China’s drive toward a lower carbon future led by Communist Party leaders who appear to have embraced the science of climate change.

Shenzhen is a high-tech hub on the front lines of efforts to reduce China’s greenhouse-gas emissions. As a low-elevation coastal city, it will be vulnerable to rising sea levels — one of the effects of climate change. (Hal Bernton / The Seattle Times)

Their actions offer a stark contrast to U.S. policies under President Donald Trump.

As a candidate, Trump repeatedly rejected the scientific consensus that fossil-fuel combustion is generating carbon and other greenhouse gases that will profoundly alter the climate. As president, he has called reviving coal production a priority and announced that the U.S. will withdraw from the Paris Agreement on climate change.

But Chinese government officials are moving away from coal, to reduce smog and the emissions that contribute to climate change and are forecast to cause big problems for Shenzhen and other low-lying Chinese cities as sea levels rise and temperatures climb.

Last year, China overtook the United States as the biggest producer of renewable energy. Green technology is a growing domestic industry and an export opportunity for Chinese solar, wind and electric-vehicle companies.

“I believe that climate change is a challenge to everyone. So there is no way back and China will push forward,” said Wang Xining, of China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Not everyone’s on board

Plenty of questions remain about how quickly and how far China can scale back its reliance on coal and other fossil fuels.

Since a 2013 peak, China’s coal consumption has dropped 7.3 percent, according to government statistics compiled by Rock Environment and Energy Institute, a Beijing-based think tank.

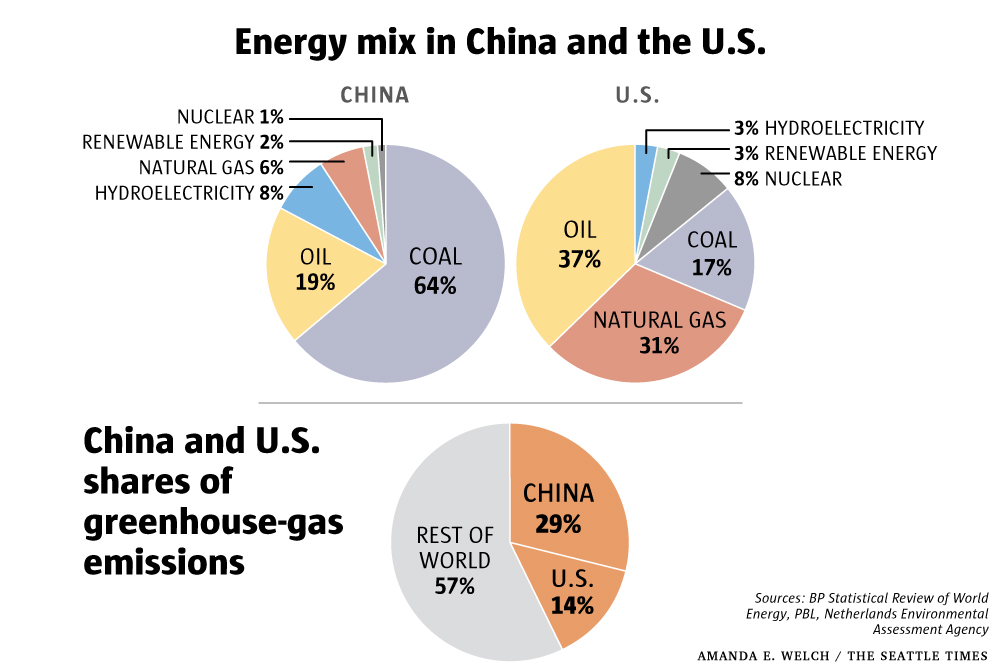

Even with the decline, China remains the world’s biggest emitter of greenhouse gases — by far. In 2015, China accounted for nearly a third of all emissions.

Coal still generates about 64 percent of China’s energy, compared with 17 percent in the United States.

As bureaucrats in Beijing try to steer the nation further away from fossil fuels, they face strong pushback. Much of the opposition comes from coal-rich regions that have long relied on the jobs and dollars that mining provides.

Regional leaders have pushed to expand the use of coal to produce chemicals and synthetic gas. And they have approved new permits for coal-fired power plants even when there was no national need for all the electricity they can generate.

“This definitely does not make the transition any easier,” said Lauri Myllyvirta, a China energy analyst with Greenpeace. “The government likes to project an image that they are a coherent entity working with one big plan. But behind that image are all the political games and positioning.”

The new construction has created a big oversupply of coal plants. On average, they operate at less than half their capacity. Their operators, eager for load, compete with wind and solar for limited space on a transmission grid that still needs major improvements to carry all that electricity to market.

Sometimes, renewable-energy projects can’t get their power to markets.

In 2016, 17 percent of China’s potential wind power was lost due to shutdowns that idled the turbines.

Support from Buffett, Gates

Part of the campaign to reduce carbon emissions involves a major shift in the economy. Communist Party leaders, in a five-year plan that runs through 2020, have called for less reliance on heavy industry and a greater focus on consumer services, higher-value manufacturing and innovative technologies such as artificial intelligence.

In Shenzhen, the transition is well underway, and the city has emerged as a testing ground for some of the policies — and technologies — that will reshape China’s energy future.

Less than 40 years ago, the sprawling urban zone that is now Shenzhen was a largely rural area on the edge of the Pearl River delta. Its biggest settlement was a small fishing village near the Hong Kong border.

In 1979, as part of a broader opening launched by reform leader Deng Xiaoping, the government declared this place a “special economic zone” for foreign investment. Shenzhen initially boomed as a manufacturing hub that drew low-skilled workers from all over China as well as entrepreneurs looking for new economic freedom.

Today, Shenzhen, with a population estimated at more than 12 million, has morphed into a kind of Chinese Silicon Valley, its economy keyed to high-tech, service and finance.

Shenzhen is home to Tencent, a social-media giant with revenue that last year topped $22 billion, and Huawei, a telecommunications company whose cellphone towers built for remote areas can include solar-powered units to operate off the electrical grid.

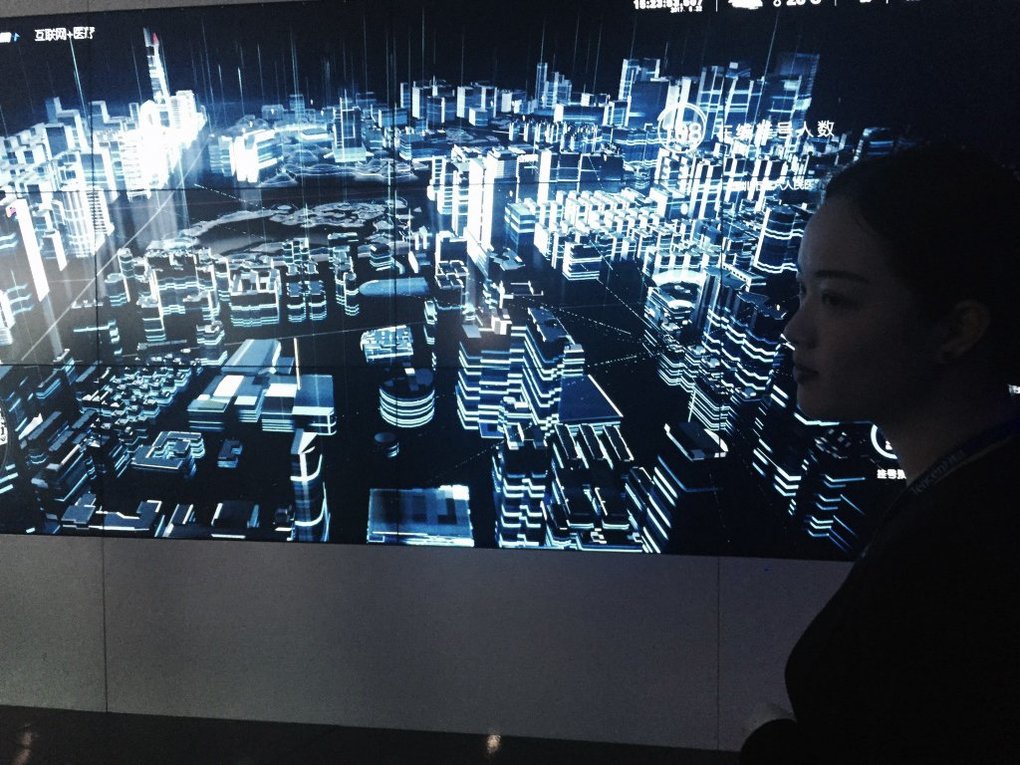

Tencent is a Chinese

social-media giant based in Shenzhen that is investing in research in

artificial intelligence, and shown here, 3-D mapping of Shenzhen.Tencent

is seeking to cut energy use at its data centers though new

conservation technologies and solar installations. (Hal Bernton / The

Seattle Times)

These companies attract young, skilled talent from China and elsewhere. Employees work in towering offices — some quirkily designed — that have sprouted along broad boulevards lined with mango trees.

Shenzhen also is the headquarters of BYD, the world’s largest manufacturer of electric cars and buses, with revenue last year of $14.6 billion.

BYD was founded by Wang Chuanfu, a chemist who in 1995 quit his job as a government researcher to found a battery company. The company captured the attention of U.S. investor Warren Buffett, whose Berkshire Hathaway took a 10 percent stake in 2008. In 2010, Buffett and Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates, who sits on the Berkshire Hathaway board, showed up in Beijing to help the company introduce a new electric car.

BYD also produces battery-storage and solar-energy systems, and its electric buses operate in dozens of cities around the world.

BYD still generates more than half its revenue within China. Much of that comes from electric-vehicle sales, which have been buoyed by government incentives and subsidies.

In Beijing, for example, consumers can buy an electric car right away, rather than wait months or years for a license plate for a gas-powered vehicle, according to Zhao Ang, a researcher with the Rock Environment and Energy Institute. Once they have the car, they can drive it five days a week to their job, and not be limited by the four-day-a-week restriction that applies to vehicles powered by fossil fuels.

By 2020, the government wants 12 percent of all new vehicles sold in China to be electric.

But the government’s big push has not come without problems.

Some manufacturers falsely inflated electric-car sales figures to collect subsidies, and late last year, government officials announced those payments would be scaled back. This year, they announced that an investigation found incidents of bribery and falsified records that defrauded the government on about 2 percent of sales.

Electric, but tied to coal

Larger concerns loom about the environmental consequences of China’s rapid expansion of electric-vehicle fleets.

Coal combustion — per unit of energy — produces more carbon emissions than burning petroleum does. So, most electric-car drivers in China — drawing their electricity largely from coal plants — contribute more climate-changing emissions than somebody driving a gas car.

“In the current system, using electric cars doesn’t have much (climate) benefit,” said Zhao, of the Rock Energy and Environment Institute.

The major exception appears to be in the southern region that includes Shenzhen.

There, coal currently accounts for only 49 percent of the power produced by China Southern Power Grid, compared with more than 65 percent nationwide.

Most of the utility’s new power comes from big hydroelectric projects, while nuclear plants account for nearly 9 percent. Wind and solar, despite a big expansion, still generate only 3.1 percent of the power.

In Shenzhen, part of the pressure to further cut fossil-fuel use comes from a government system — launched in June 2013 — that sets limits on carbon pollution. The limits get tougher over time for 636 polluters that represent less than half the city’s emissions.

Such efforts have been a hard political sell in the United States. In Washington state, a state rule backed by Gov. Jay Inslee to cap emissions faces legal challenges.

China has established experimental programs in Shenzhen and six other areas, and a national plan is expected to be rolled out later this year.

“It’s not an easy process, and there are compromises being made,” said Lin Jiaqiao, a Rock Environment and Energy Institute researcher who tracks carbon markets. “But by the end of this year, I think it will be established for sure.”

Reaching for global markets

For the Chinese government, part of the payoff for investing in green technology is the opportunity to claim global markets as demand for renewable energy expands.

China is the dominant manufacturer in the solar industry, and unlikely to relinquish that position anytime soon. Chinese companies are an important provider of wind turbines. And BYD aggressively promotes its technologies around the globe with international assembly operations that include a Southern California plant employing some 600 people.

Even as China struggles to decrease its dependence on fossil fuels, Chinese institutions continue to fund the construction of new coal plants in other countries, including billions of dollars of new projects in Pakistan.

Some within the government are now calling for a greener development policy, but it’s uncertain how much clout they have.

“That’s definitely something that hasn’t been settled right now,” says Myllyvirta, the China energy analyst with Greenpeace. “There’s a lot of money going into building coal plants abroad … But, at least the debate has started.”